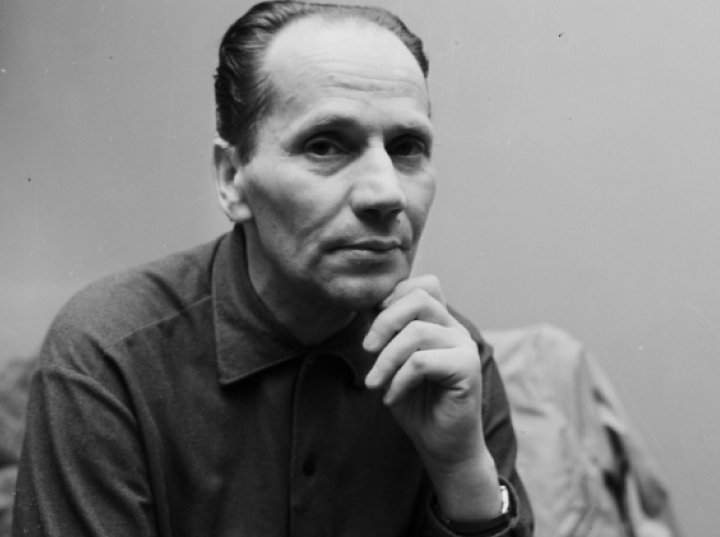

“Miron – Poland’s greatest private poet” – wrote prof. Mary Janion. June 30 marks 100 years since the birth of the author of “Obroty Rzeczy”, “A Diary from the Warsaw Uprising” or “Chamowo”. Tadeusz Sobolewski notes that “Miron depicts the world as if he is seeing it for the first time every time”.

“Białoszewski has the ability to accept what he is, all his work is about getting rid of himself, the attitude of a yogi, an Eastern sage,” wrote his friend Tadeusz Sobolewski about Białoszewski. Białoszewski describes the world a bit as an alien seeing Earth and its inhabitants for the first time. He knows nothing about the planet, he has no predetermined hierarchy of issues. He sees and everything he sees seems equally important to him – politics and cracked windows, the color of snow and stories heard. At Miro there is a great acceptance of being who you are “- Sobolewski added.

“Miron – Poland’s greatest private poet” – wrote prof. Mary Janion. The consequence of this attitude was Białoszewski’s distance from politics, as well as from the democratic opposition of the Polish People’s Republic. “Young people without experience think that something fundamental can change in the system. They do not know that borders and system changes occur only through hell and war. It costs a lot” – writes the author of “Diary of the Warsaw Uprising” in “The Secret of Dziennik” .

Miron Białoszewski was born on June 30, 1922 in Warsaw in Leszno (some sources mention July 30, birth certificate is lost, the poet never sets the exact date). His father was a postal clerk, his mother – a seamstress. At the outbreak of World War II, the future poet was a student of the third grade of the gymnasium. He graduated from his high school diploma in secret classes, then began studying Polish at the secret University of Warsaw. After the rebellion surrendered, Miron and his father were taken to a temporary camp in Ambinowice, from where they managed to escape. In February 1945, Białoszewskis returned to Warsaw.

Białoszewski found work at the Main Post Office, then as a journalist at “Kurier Codzienny”, “Wieczor Warszawy” and “Świecie Młodych”. In the spring of 1955, he co-founded the Na Tarczyńska Theatre, where he staged his stage programmes, including. plays “Vivisection” and “Osmędeusze”. The avant-garde and experimental theater in Tarczyńska was at that time an extraordinary phenomenon: it existed outside the official, controlled and “nationalized” culture. It was the personal endeavor of three poets: Białoszewski, Bogusław Choiński and Lech Emfazy Stefański – owners of the flat on Tarczyńska Street, where the texts of all three were staged.

Białoszewski belongs to the so-called “Współczesności” generation, he made his debut in Krakow’s “Życie Literackie” in 1955, a year later his first volume – “Obroty Rzeczy” (Obroty Rzeczy “). Then among others “Calculus parochial” (1959), ” Mylneemosi” (1961) and “That was and was” (1965), which brought him publicity. Thanks to the efforts of his friends, he accepted an apartment in Dąbrowski Square in Warsaw, where he lived with his life partner, the painter Leszek Soliński. Their relationship was the reason why Białoszewski was expelled in 1953 from the editorial office of “Świat Młodych.” After the disbandment of Teatr na Tarczyńska, Białoszewski founded the Osobny Theater in an apartment on Dąbrowski Square with Ludwik Herling and Ludmiła Murawska, which operated until 1963.

Overall, as well as the beginning, of Białoszewski’s work, one can see his creative attitude towards language. “The author still exerted a great influence on Polish literature. His poetry changed the relationship between spoken and written Polish, and spoken language began to be used more often in literature. It also changed attitudes towards what was avant-garde. Avant-garde may not be just some great theory which has revolutionized the world, as the avant-garde of the interwar period argued, but could also be just a joke, a ludic and innovative approach to language,” says Prof. Anna Nasiłowska of Białoszewski.

In 1970, Białoszewski’s most famous work was published, “Pamiętnik z Warszawskiego Uprising”, in which the author, 26 years after the nightmare of war, describes his experiences. On August 1, 1944, Miron Białoszewski was in Wola, where he survived the first days of fighting. Then, he made his way to the Old Town, from where on September 1 he went through the sewers to ródmieście, leading the wounded rebels. The author was 22 years old during the rebellion, unlike many of his colleagues from the Columbus generation – he did not fight. His account created images of the Warsaw Uprising that were watched by ordinary people. There is no pathos, no heroic struggle or no war adventure atmosphere here. The world is presented with a world of dungeons, gates, courtyards, makeshift kitchens, and collective dens. Białoszewski himself explained the purpose of his book as follows: “I want everyone to know that not everyone shoots, I want to write about the universality of rebellion”.

Miron Białoszewski waited 23 years to describe the rebellion. He himself wrote: “For twenty years this subject crushed me. I thought about its form, but it was too close, or I remembered too many things. It seems that I cannot possibly translate into language, something that is still open, it is impossible to close in form. And then I knew it should be simple, regardless of form. Just sit back and write.” For many, Białoszewski’s account of the Rebellion is hard to accept, due to his complete resignation from pathos and the narrator’s focus on the details of everyday life. Wojciech ukrowski wrote in a book review: “Can be shortened by 50 pages or dragged by 100 pages, the form and effect will not change. Once we get used to Białoszewski’s chirping, a feeling of monotony grows, and then disappointment and anger come, why does he drive his protagonist out of his mind, turning him into just a digestive tract, fear with amputated memory and the ability to get along, embryos floating in other people’s solutions fighting, reflexively grimaced and looked for mother. “

Other critics, however, note the value of Białoszewski’s text. Maria Janion writes: “Białoszewski’s diary of the Warsaw Uprising, which abandoned the field of + sanctity + war completely and radically turned commonplace, rationalizing it – if only by chance! – is one of the exceptions. […] By depicting the death of the City, Białoszewski reaches the pinnacle of the masterpiece. […] He repeats nothing for anyone – by reaching the core of the reality of war, exploring the essence of things phenomenologically, he discovers his form of sovereignty for war, both personal and social.

Then, the next volume of prose appeared, incl. “Donosy ycia” (1973), “Szumy, zlepy, string” (1976) and “Zawał” (1977). Białoszewski wrote “Chamowo” from June 1975 to May 1976. He then moved from Dbrowski Square, where he lived with Le, namely Leszek Soliński. However, they decided to live separately. Białoszewski moved to a new block on Lisbońska Street, namely in Chamowo, as residents around Saska Kępa call this part of town behind Trasa azienkowska. “A large house, ten stories high, a quarter of a kilometer long, stands gray and empty. In the courtyard of the shell. Between the house and the azienkowska Route, there are neither squares nor meadows. Le said – there is no pond here, but they had buried it a poplar, across the meadow diagonally “- this is how Białoszewski wrote his first impressions of Lisbońska Street.

When Białoszewski moves to Lisbońska Street, he is reading “Robinson Crusoe” – the part where the protagonist only knows the island where fate has thrown him. Białoszewski feels like Robinson – thrown into a whole new reality, among strangers. “Chamowo” describes, step by step, day by day the poet explores a new place and grows into an unfamiliar environment. Tenants are gradually moving into blocks, more blocks are built, traces of old buildings disappear. The poet was not completely used to the new place of residence, he felt a bit strange in Lisbońska until the end.

It was there that he wrote the “Secret Diary”, which, due to the degree of honesty and self-disclosure, was published only 29 years after the poet’s death. Readers of the “Secret Diary” have contact with Białoszewski’s circle of friends, his “trial”, as Tadeusz Sobolewski describes in the introduction to the book – one of the heroes of this record. The poet’s friend – Ludwik Hering, Ludmiła Murawska, joked: “With Miro, as in UB, you have to be careful what you say, because he records everything in his memory, then he will describe”, “when he suddenly suddenly went to the bathroom during a meeting, had to for this to take down the dialogue”. Reading the “Secret Journal” shows that they are right – their little things in life, conversations about shopping, slamming windows, even summaries of their dreams, are captured. The diaries of “Escy” are Sobolewskis – Anna, Tadeusz (film critic) and their little daughter Justynka (now literary critic). Jadwiga is Mrs Stańczak, blind mother of Anna Sobolowska, her apartment is on ul. Hoża is the scene of many scenes from “The Secret Diary”. Kitty Kocia (known as the protagonist of “Kici Koci’s Cabaret”) is Halina Oberlaender, painter and set designer, her mother Białoszewski christened Sybilla Grochowa. Maria Janion (named by Białoszewski prof. Misia), Maryla migrodzka and Małgorzata Baranowska appear on the pages of the “Secret Journal” as “educated women” aka “Three Eumenids” (i.e. goddesses – avengers), because “when they chase someone, they don’t leave dry thread on it”, wrote Białoszewski.

In “Secret Diary”, Białoszewski also writes directly about his adventures and love. From 1950 he was associated with Leszek Soliński, the figure of Jot, also known as Piwek, Miron’s lover, appeared on the pages of The Secret Diary. Białoszewski wrote that at first he considered his “gay needs temporary”. “At 15 or 16, I asked myself + when +. Am I going to change from day to day? No. So you have to accept yourself as you are.

On the one hand, Białoszewski yearns for loneliness, but sometimes he gets sick of it and then he will visit friends, often in the afternoon or evening, because he lives a nightlife. He hated the sun so much that it darkened the windows. The poet was not very fond of alcohol, but often used preparations with psychedelic and codeine, incl. tussipek syrup.

The records of the “Secret Diary” were interrupted on April 22, 1983, when Białoszewski felt unwell and was transferred to the rehabilitation department of the Cardiology Institute in Anin. He died suddenly on the night of June 17-18, at the house of Jadwiga Stańczakowa, a blind friend to whom he dedicated his “Secret Diary”. (PAP)

Author: Agata Szwedowicz

aszw / skp /

“Reader. Future teen idol. Falls down a lot. Amateur communicator. Incurable student.”