130 years ago, on April 1, 1893, the National League was founded – an organization that was the beginning of the modern national camp, whose programmatic goal was to represent the Polish nation in all three partitions and win Poland complete independence.

For the first two decades after the defeat of the January Uprising, political life in the Kingdom of Poland froze. An idea capable of reviving the dream of independence did not appear on the horizon. Small socialist circles consciously withdraw from referring to the issue of independence, considering the main postulate of the emancipation of workers. It also appears that the formally apolitical positivist program which, according to its critics, could have led to the consolidation of obedience to the colonialists, failed. The impetus to revive the idea of independence came from emigration circles, who criticized the growing sentiment of loyalty to the colonialists.

In 1887, a copy of the Paris brochure entitled “On Active Defense and National Wealth” arrived in Warsaw. The author hides under the pseudonym “ZFM”. The patriots to whom the brochure addressed knew that underneath was Colonel Zygmunt Fortunat Miłkowski, a veteran of the January Uprising and a novelist. Miłkowski put forward the postulate of “active defense”, that is, the rejection of any form of “agreement”. Its ultimate goal is to regain full independence, inter alia, through armed uprisings that begin at the outbreak of war between the dividing powers. Miłkowski and his friends believed that Russia and Germany were on the brink of conflict. “This is not a +romantic+ rebellion, but a rational one, applied to foreseeable opportunities and adapted to the patterns and similarities of how the Prussian headquarters prepared for events that might and supposedly appear on the European political horizon” – the pamphlet argued. In August 1887, a group of emigration activists, at a meeting in Switzerland, founded the Polish League. The program is a repetition of the postulates from the brochure mentioned above by Miłkowski.

The ideas proposed by Miłkowski will be transferred to Polish territory under the division by Jan Ludwik Popławski and Zygmunt Balicki. The first to attempt to create a secret patriotic organization dates back to the 1970s. After being captured by the Russian gendarmerie, he was sentenced to eight years of exile, but after a few months he managed to return to the Kingdom of Poland. Zygmunt Balicki was active in the socialist movement that emerged from the early 1980s, but under the influence of Miłkowski’s arguments he decided to become an activist for the Polish League in a country divided by the forces of partition. In 1887 he came to Kraków. There, taking advantage of Galicia’s relative political freedom, the Polish Youth Union was founded, which later operated under the code name “Zet”. Initially, the organization gathered independence supporters, also with views similar to socialists. Only later did “Zet” acquire a clear political identity.

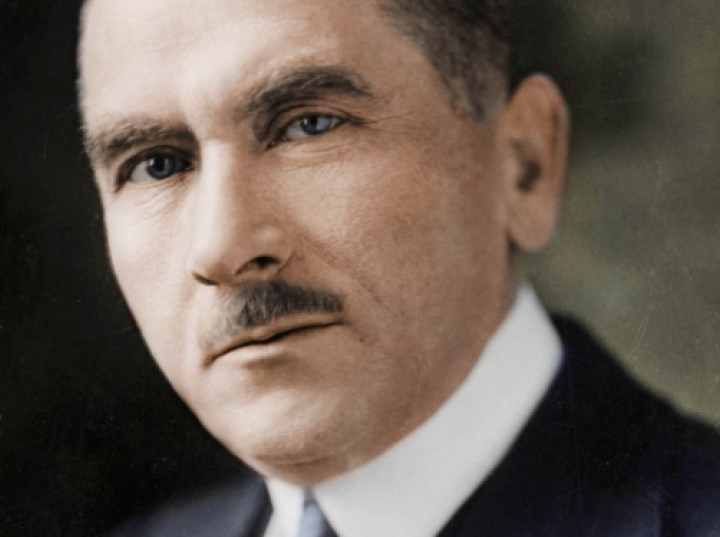

One of the first activists of “Zet” was a biology student at the Imperial University of Warsaw, Roman Dmowski. The future leader of the National Democracy soon became the head of the “ZET” in Warsaw and a member of the emigre and interpartite Polish League. On May 3, 1891, a parade organized by “Zet” marched through the streets of Warsaw on the anniversary of the adoption of the 1791 Constitution. It was the first patriotic manifestation in the Kingdom since 1863. At that time, Dmowski, thanks to a scholarship from Kasa Mianowski, left, officially for scientific purposes, to Paris. The real aim was to strengthen contacts with Popławski and Balicki. Along the way, he discovered the realities of political life in Galicia, which were different from the rivalries of the congress, and which disillusioned him because of the prevailing conservative tendencies.

On August 12, 1892, returning to Poland, he was detained by the tsarist police for his participation in the May 3 demonstration a year and a half earlier. The five months incarceration in the Warsaw Citadel was a chance for Dmowski to rethink his next steps on the political path.

Waiting for the verdict of the court in general, together with the younger generation of the emerging political environment, he set about creating a new organization, which on April 1, 1893 took the name National League. The date can be treated as the symbolic beginning of the creation of the modern national camp, whose programmatic goal was to represent the Polish nation across all three partitions, and in the long term – to regain independence. In the same year, the League published its program declaration “Our Patriotism”, in which Dmowski wrote: “Every political act of the Polish people, wherever it is committed and against whom, must have in mind the interests of the whole nation.” Dmowski as leader of the entire Polish independence movement.

In the autumn of 1893, Dmowski was sentenced to leave the Kingdom of Poland for five years. After two years of exile, with the help of friends, he made his way to Galicia illegally. He settled in Lviv, where he became an assistant to the renowned zoology professor, January Uprising rebel Benedykt Dybowski.

In the first years of its existence, the National League had only a few hundred members in all three partitions and in exile. However, dozens of local and cross-partition organizations grew up around it – people’s societies, sports associations, paramilitary organizations, women’s organizations – and many magazines promoting patriotic ideas. In 1902, in one of them, Przegląd Wszechpolski, the episode “Thoughts of a Modern Pole” was published. Dmowski’s work is something between an ideological manifesto and a commitment to political journalism. As the author himself claims, the recipients are not those who “need to be won over to become Polish”, but Poles with a crystallized national identity. “I am Polish – meaning I belong to the Polish nation throughout its territory and throughout its existence, both today, in past centuries, and in the future; it means I feel my close connection with all of Poland: with today […]; with the past – with that which only a millennium ago emerged, gathering around itself native tribes without political individuality, and with which, in the middle of its history, spread widely, threatening its neighbors with its power and swiftly walking the paths of civilization’s progress, and with those that later plunged into decline, caught up in the stagnation of civilization, preparing itself for the disintegration of national power and the destruction of the state, and with which it then fought unsuccessfully for freedom and the existence of an independent state,’ he argued.

By the time Dmowski was writing Thoughts on the Modern Pole, his political camp had finally crystallized and his last ties to pro-independence leftists had been severed. They differ in their ideas and views on the methods of struggle for the reconstruction of the country. Dmowski’s opponents then began to regard him as a pro-Russian politician. However, his opinion contradicts the diagnosis. In 1905, in Przegląd Wszechpolski, Dmowski published a series of articles which were highly critical of Russia. In it, he presented Russia as a passive mass living under the yoke of a degenerate Asian despotism. He did not believe in the success of any constitutional reforms that changed the imperial system. He believed that they could only delay the collapse of the Russian statehood. Therefore, he decided that limited reforms of the weakened Russian state after the defeat in the war with Japan and the revolution of 1905 should be used to create a strong and legally operating Polish representative in the State Duma. A few years later, in 1917, in a private letter to Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Dmowski brutally described his parliamentary activities as “brothers to cattle” for the Polish cause. The strategy proved successful. Dmowski’s camp gained a dominant political position in the Kingdom of Poland and gave him a mandate to represent the Polish cause at the outbreak of World War I. (PAP)

Author: Michał Szukała

szuk/ aszw/

“Reader. Future teen idol. Falls down a lot. Amateur communicator. Incurable student.”