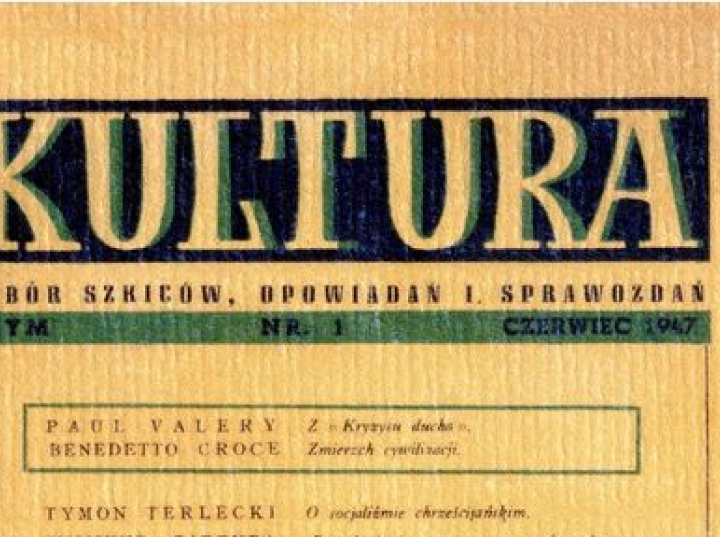

75 years ago, on June 20, 1947, the first issue of Kultura, one of the most important Polish emigration magazines, was published in Rome. The ideas expressed in it had a great impact on the attitude of the independent intellectual elite in the Polish People’s Republic and shape Polish foreign policy to this day.

The end of World War II raised questions for the soldiers of the 2nd Polish Corps about returning to a country ruled by communists. For many young intellectuals who followed in the footsteps of the Anders Army, this path was closed. The mood among many of them was very bad. “We entered into some incredible chaos. Who knows Wacek Zbyszewski is right [redaktor sekcji polskiej radia BBC – przyp. PAP]that this is the beginning of the end of the world,” wrote Jerzy Giedroyc, a pre-war publicist who supported Sanacja, in February 1946, in a letter to Zofia Hertz, a collaborator of the “Orzeł Biały” editorial office.

Already in March, Jerzy Giedroyc, together with Józef Czapski, Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, and Zofia and Zygmunt Hertz, founded the Institute of Literature in Rome. They all have publishing experience from the 2nd Polish Corps Ministry of Press and Publishing, as well as great journalistic and literary talents. Thanks to the funds donated by the 2nd Corps, printing equipment was purchased. The budget of the new publishing house was complemented by the efforts of Zygmunt Hertz, which traded gasoline from military stockpiles.

The selection of the first work published in Rome was no accident. Among them are the “Book of the Polish Nation and the Pilgrimage of Poland” by Adam Mickiewicz. It was a sign that the community gathered in Rome was trying to speak out on behalf of the new great Polish emigration and to program its activities. The introduction to the “Book” was written by Herling-Grudziński. He appealed to choose a new direction for the romantic drive and struggle for freedom waged by “all living people who feel truly European thanks to this war”.

Culture wants to seek in the world a Western civilization that will live, without which Europeans will die, just as the main layers of the former empires died, ”writes in the introduction. In the pages that follow, prominent intellectuals – Paul Valéry, Benedetto Croce and Tymon Terlecki, as well as highly talented but unknown journalists such as Andrzej Bobkowski and Józef Czapski – publish their voices in discussions about the future of Europe.

The thread of the unity of European civilizations appeared on the pages of Kulture in its first issue published on June 20, 1947. “Culture wants to seek in the world a Western civilization that will live, without which a European will die, just as the leading layer of the former empire dies. “- it is written in the introduction. In the pages that follow, leading intellectuals – Paul Valéry, Benedetto Croce and Tymon Terlecki, as well as highly talented but unknown journalists such as Andrzej Bobkowski and Józef Czapski – publish their voices in discussions about the future of Europe .

Criticism is given to the European schools of thought that supported the Soviets, incl. Sartre’s existentialism. Instead, oppressed by Italian fascists, Croce proposed a stance against all totalitarianism, which “does not detract from the fullness of one’s spiritual life and turns away from the principle of survival which is lame and vile at all costs.”

It was no coincidence that “Kultura” was despised by the Italian communists as a center hostile to their ideology. Giedroyc came to the conclusion that publishers should be moved to a more politically stable country. In October, the Literary Institute group reached Paris. There, too, they faced communist hatred, incl. gathered at the editorial office of the pro-Soviet daily “L’Humanité”. In 1949, Giedroyc explained the disappearance of the first edition of Na nieludzkiej wiata Czapski by purchasing the entire edition by Soviet agents. The Left reacted with equal anger to the publication of Czesław Miłosz’s “Captive mind”. Years later, the eminent historian of Central Europe, Daniel Beauvois, said that in the 1950s, the Paris intellectual community defined Kultura as a fascist journal. “This Moscow tale was taken for granted in Poland for a long time, and it was the intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968 that started a change of mind” – he recalls. Only after reading Kultura did the vision of Central Europe presented there have a decisive influence on the perception of this part of the continent.

In 1954, a villa in Maisons-Laffitte near Paris became the centerpiece of the Literary Institute. In the first years of operation in France, Giedroyc formed his community programme. He stated that “Kultura” could not be a direct participant in emigration disputes, but his task was to inspire Polish politics both within the country and among emigrants. “I have no, and never have, purely literary or editorial ambitions, like Grydzewski, for example. [Mieczysław, redaktor londyńskich „Wiadomości” – przyp. PAP] […] Culture is only a tool, not an end in itself,” he said in 1950 in an interview with one of the emigration activists in the US.

In many of his statements, he distanced himself from the increasingly fragmented and divided strife in London. Parisian culture was also distinguished from the legalist community by the belief that a communist system could develop in the Polish People’s Republic towards greater assistance to enslaved peoples. That is why Giedroyc and his entourage greeted the October 1956 thaw with high hopes. Gomułka’s attitude quickly disappointed them, so after a few years they saw some hope in revisionist circles who believed in “human-faced socialism”. In 1971, Leszek Kołakowski stated in his “Thesis on Hope and Despair” that communism is fundamentally unreformable, but can change its character under the influence of social pressure. Thus, the emergence of open opposition in 1976 in Maisons-Laffitte was accepted as a turning point in Poland’s fate.

Giedroyc has repeatedly emphasized that the aim of his activities is to build even the smallest understanding with the state. “It’s nothing that we haven’t read every issue of +Kultura+ and every book of the Literary Institute. From the fragments that have come down to us, the intended whole must have been remade,” wrote Jan Józef Lipski in 1987.

The opposition also received the program’s most important articles on Eastern affairs. In 1974, Juliusz Mieroszewski published one of his most important articles, entitled “The Polish Russian Complex and the ULB Area”. Under this abbreviation, the author understands the areas that once belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus. “The notions of self-determination and freedom for our fellow nations separate us from Russia, while sincerely rejecting the imperialist plans, which include the hope of settling with Moscow over the head and at the expense of those countries – such a program can restore the lofty motives of Poland’s independence policy . morals “- explains Mieroszewski.

The appearance of a text on policy towards the ULB shocked the London emigrants, who uncompromisingly held the position of having Poland on the eastern border before 17 September 1939. Attention was also paid to the anti-Polish hatred that existed among the country living between Poland and Russia. According to Mieroszewski, the elites of these countries must work to break down barriers to cooperation. The stakes are the independence of Poland and the ULB countries. Giedroyc himself argued that the aim of such a policy should also be to establish the position of these nations among European states. “We must realize that the stronger our position in the East, the more important we are in Western Europe,” he stressed.

Despite political and philosophical differences, Giedroyc and his entourage are appreciated for their dedication. “He identifies with his work in such a way that it is impossible to imagine him without it. Because it’s also more than a job. For Giedroyc, being an editor is a way of being and acting, an attitude towards Poland and the world ”- this is how his friend and colleague Krzysztof Pomian characterizes Giedroyc. Notable is the distance the editor creates between himself and his surroundings; even with close associates, he turns to “you” only after many years of acquaintance. On his office door hung a sign engraved with the Latin phrase, “Gua hominem,” which means “Beware of men.” Giedroyc kept his personal life to himself. He even openly claims that he has no private life.

In “Kultura” and in other publications of the Literary Institute, much space is devoted to history, which is considered the key to understanding the present and the future. In 1962, the “Kultura” community began to publish a magazine dedicated to recent history – “Zeszyty Historyczne”. The purpose of their creation was not only to present a censorship-free historical vision of the communist regime, but to understand the goals of the Soviet empire. “70 percent or even 80 percent of politics is a discussion of history. Neither of us knows exactly what members of the Kremlin’s political bureaus talked about during secret meetings. Neither of us knows what Brezhnev is thinking and planning deep down. However, we know from history what his predecessors thought and planned over the last two hundred years. We conclude that Brezhnev thinks similarly to his predecessors, because in reality nothing has changed, ”wrote Mieroszewski.

Maisons-Laffitte, December 13. Without words. Regardless of the date, not a word,” wrote Gustaw Herling-Grudziński in “The Diary Written in the Night.” The suppression of the “Solidarity” legal movement was a surprise to “Kultura”, but Giedroyc judged the possibility of a “rotten compromise” between parts of ” Solidarity” and the regime as a far greater danger to Poland. Very critical was written about the diocese, which, in Giedroyc’s opinion, could be the protector of such a deal. In the late 1980s in Maisons-Laffitte, opposition leaders who, according to Kultura, had to give way to younger and more radical underground activists, were the most critical of the opposition. Giedroyc considered the roundtable a disaster. After several years, he revised his opinion, but he is still very critical of Poland’s transformation, especially during Lech’s presidency Wałęsa, which he considered a period of missed opportunity.

The end of the twentieth century was the time when the creators of the next “Kultura” left. In 1993 Józef Czapski died, on 4 July 2000 Herling-Grudziński. Just a few months later, on the night of September 14-15, 2000, Giedroyc died. “Nostalgia for the dreamed, idealized, almost perfect Poland, is intensified at the end of the Editor’s life, when it seemed that his goal was near and its fulfillment possible. Hence Jeremiah’s bitter note, hence sharp and impatient criticism: the dream is silent and only a dream, ”said Fr. Henry Hoser.

According to Giedroyc’s will, the next edition of Kultura will be the last. Zofia Hertz became head of the Literary Institute. Historical Records are still being published. Their editor-in-chief, Henryk Giedroyc, decided in 2010 to close the journal. Jerzy’s brother didn’t live to see the final issue – he died on March 21, 2010 in Maisons-Laffitte. Kultura’s most important editors – Jerzy Giedroyc, with his wife (until 1937) Tatiana Szwecow, Henryk Giedroyc, with his wives Leda Giedroyc, Zofia and Zygmunt Hertz, Józef Czapski and his sister Maria – rest at the cemetery at Le Mesnil-le-Roi near Paris ( PAP)

Author: Michał Szukała

search / skp /

“Reader. Future teen idol. Falls down a lot. Amateur communicator. Incurable student.”

![Bogusław Wołoszański: “Achieving nuclear weapons would be the beginning of World War III” [WYWIAD]](https://storage.googleapis.com/bieszczady/rzeszow24/articles/image/877236c0-66fd-457a-9eb4-41792f9077ff)