Russia’s war in Ukraine and the attitude of other countries towards it may at first glance seem like a duel between democracy and autocracy. However, closer inspection shows that this is misleading.

This is well illustrated by the country’s vote in the UN General Assembly, which suspended Russia’s membership of the Human Rights Council. The main reason was allegations that Russian soldiers killed civilians. Russia later withdrew.

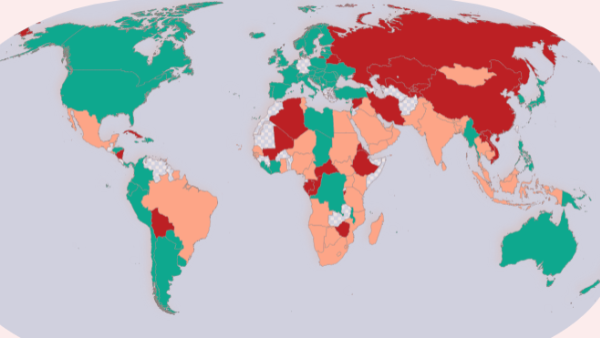

The resolution, which was initiated by the United States, achieved the two-thirds majority of the members required for adoption. 93 countries in favour, 24 against and 58 abstentions – their votes do not count towards the final.

Interaction of world democracy does not happen

Of course, most of the democracies condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and also voted to suspend its membership in the UN Human Rights Council. But perhaps the most populous democracy in the world, India, abstained – as did the largest democracies in Latin America in Brazil and Mexico.

India is one that puts national interests ahead of idealism. After all, he gets most of his modern weapons from Russia. “India is dependent on arms imports from Russia and also has nuclear power as its neighbour, Pakistan,” explains Pavel Havlíček of the Association for International Affairs (AMO) for the Report List. “In addition, it imports huge amounts of fertilizer from Russia, which is critical to the livelihoods of billions of people.”

Similarly Brazil or South Africa have trade relations with Russia which are not critical but significant. South Africa even identified NATO’s expansion as Russia’s reason for provoking war.

The only functioning democracy in the Arab world, Iraq, once again abstained from voting on a UN General Assembly resolution condemning the Russian invasion. Russia is also not criticized by Asia’s second-largest democracy, Indonesia.

A closer look at Asian countries shows that Russia’s exclusion from the international community is considered somewhat ambiguous. From an East Asian perspective, this is – simply put – war in a country thousands of miles away.

Fareed Zakaria, an American political scientist of Indian descent, points out that “the idea of a grand ideological campaign against the autocracy makes most developing countries nervous. “Many of them have strong economic ties to China and are closely linked to other autocratic regimes around them.”

How to frame the world today?

According to Zakaria, the current division of the world can be understood as countries that believe in an international order based on rules and those that do not. “Russia has emerged as the world’s leading rogue state, intent on attacking the very essence of this order: the norm that borders are not changed by force. Moscow is trying to return to the realm of pure power politics, where, in Thucydis’ words, the strong do what they can and the weak tolerate what they have to do.”

Zakaria was referring to former British Foreign Secretary David Miliband, who saw the division of the world based on international rules as far more diverse than the division of democracy versus autocracy.

Singapore, for example, is not a fully-fledged liberal democracy, but has consistently supported international norms and values. At the start of the Russian invasion, he decided – for the first time in more than 40 years – to join international sanctions, even though the UN Security Council did not overthrow him because of Russia’s veto.

European optics lost in the world

Pavel Havlíček of AMO also opposes the simple division of the world into democratic and non-democratic. “Not only Asian but also Latin American countries view the war in Ukraine as less principled, but more pragmatic. In African countries, there is also an antipathetic effect on the former colonial powers. From the point of view of previously colonized countries, it might be accepted that Russia is trying to weaken their influence.”

“Tv nerd. Passionate food specialist. Travel practitioner. Web guru. Hardcore zombieaholic. Unapologetic music fanatic.”