Tuvia Tenenbom himself was born into the Orthodox community in Israel. But he was looking for something more. He came to America thinking that in a free land he could finally say and do what he wanted. He gradually understood that he was lying to himself.

He remembers when he first arrived in New York, he could read both conservative and liberal commentary in the newspapers. First, the conservatives disappeared from mainstream newspapers, then gradually the liberals also disappeared. Both have been replaced by “Puritan extremists,” he notes sadly. A new religion is slowly being born, whose characteristics include sexual puritanism, gender sensitivity, veganism, and a culture of cancellation.

So now the writer goes in search of “something more” in the opposite direction, home, to the orthodox Jerusalem neighborhood of Mea Šearim. Tenenbom chooses a problem in each chapter. For example, why does the orthodox say men shouldn’t look at women? Why can’t she hear him sing? Why was she dressed as she would in medieval Europe, in a caftan and with a thick headband on her head, even though it was thirty-five degrees?

He visited various rabbis and sages from whom he sought explanations. They often reply that the Talmud (a collection of rabbinic discussions on Jewish law, ethics, editor’s note) asks for it. When he does insist on citing a particular quote, though, it’s usually hard to find. He eventually discovered that the Talmud contained many and often conflicting opinions.

In the holy texts, Tenenbom also finds descriptions of how young people in the past enjoyed fun and wild parties celebrating sexuality in vineyards. Why is the contemporary Orthodox world so stiff, bitter, and polite? The author conducts dialogues with hundreds of people, simple people and rabbis, poor and rich. He often unsettled them with witty questions and exposed many hypocrisies and panders.

As he passed various temples and schools, he heard claims that they were the only true Jews. The others from the next school weren’t real Jews, sometimes they were even crooks or charlatans. In the Orthodox quarter, he met a musician who explained to him that the songs he grew up listening to and which he always associated with the Yiddish language, with psalms, with Judaism, were Romani. Jews absorbed a number of cultures, Ukrainian, Polish, Hungarian, German. Claiming something is original nowadays tends to be highly moot.

In the world’s most orthodox, to which ordinary Israelis are not at all fond of, the writer comes to the bitter realization that they are not much different from New York progressives. They have their own religion, a strange set of rules and unsubstantiated claims. Despite this, they are very kind and friendly people.

The message of this book is not to reject dialogue, to reject fanaticism. And even though it can be tough, keep a sense of humor.

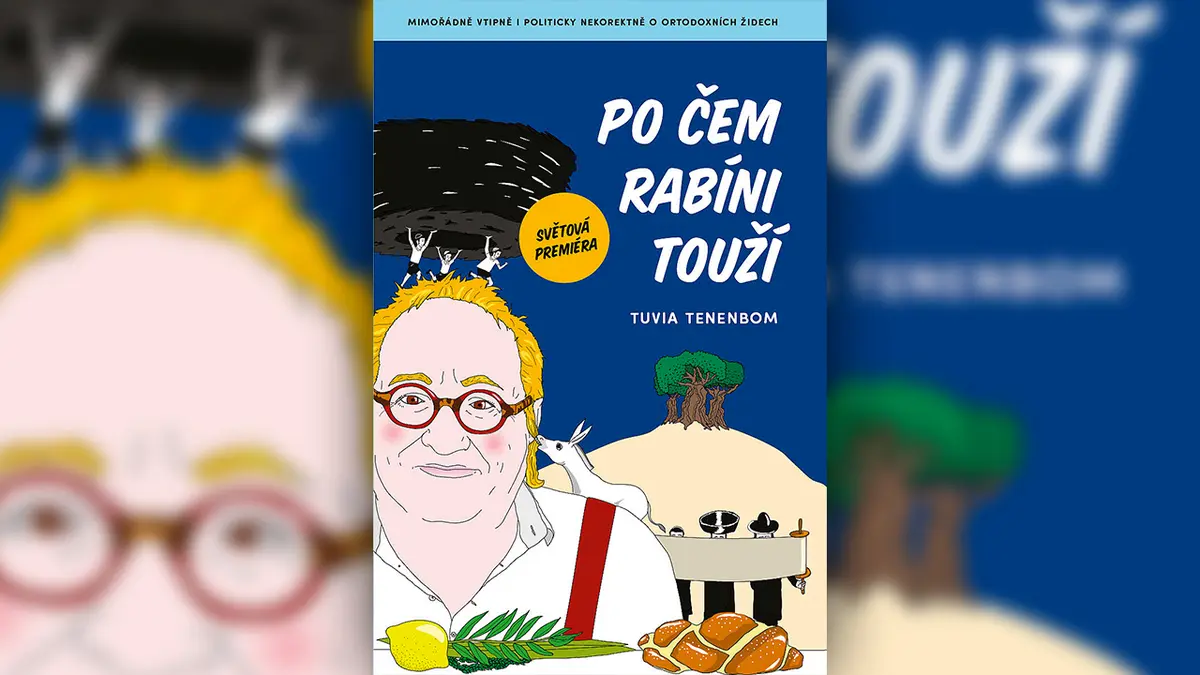

| Tuvia Tenenbom: What the Rabbi Wants |

|---|

| Walls, translated by David Weiner, 472 pages, 359 CZK |

| Rating 75% |

“Unapologetic social media guru. General reader. Incurable pop culture specialist.”